The Codex Seraphinianus: How Italian Artist Luigi Serafini Came to Write & Illustrate “the Strangest Book Ever Published” (1981)

The Codex Seraphinianus is not a medieval book; nor does it date from the Renaissance along with the codices of Leonardo. In fact, it was published only in 1981, but in the intervening decades it has gained recognition as “the strangest book ever published,” as we described it when we previously featured it here on Open Culture a few years ago. Since then, Rizzoli has published a fortieth-anniversary edition of the Codex, which author-artist Luigi Serafini has granted interviews to promote. What new light has thus been shed on its more than 400 pages filled with bizarre illustrations and indecipherable text?

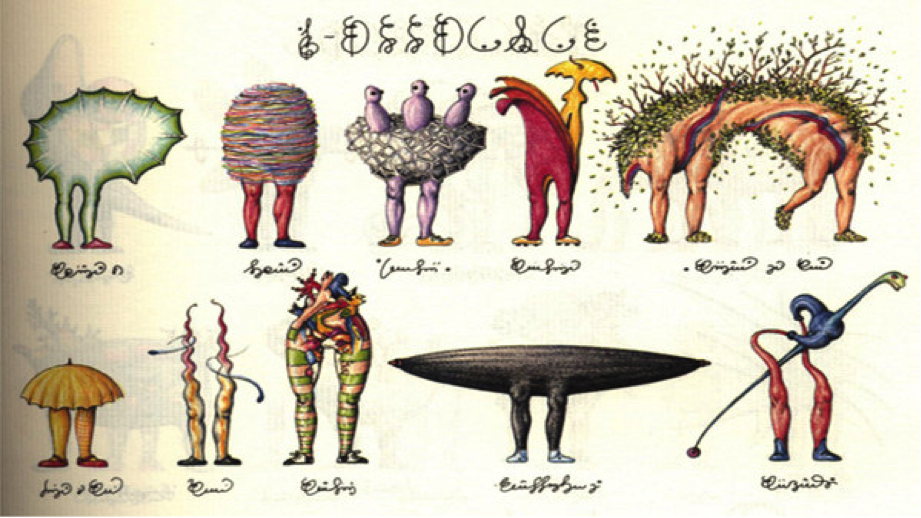

“The book is designed to be completely alien to anybody who picks it up,” says the narrator of the Curious Archive video at the top of the post. “Not only are the images utterly mind-bending, it’s written in a made-up and thoroughly untranslatable language. And yet, the more you read, the more you might find a strange sense of continuity among the images. That’s because Serafini intended this book to be an encyclopedia: an encyclopedia of a world that doesn’t exist.”

The experience of reading it — if “reading” be the word — “reminds me of being young and flipping through an encyclopedia, staring at pictures and not comprehending the words, but feeling a strange, untranslatable world hovering just outside my understanding.”

Serafini himself describes the Codex as “an attempt to describe the imaginary world in a systematic way” in the Great Big Story video above. To create it, he spent two and a half years in a state he likens to “going in a trance,” drawing all these “fish with eyes or double rhinoceroses and whatever.” These images came first, and they were all so strange that he “had to find a language to explain” them. The resulting experience lets us experience what it is “to read without knowing how to read” — an experience that has attracted the attention of thinkers from Douglas Hofstadter to Roland Barthes to Serafini’s countryman Italo Calvino, a man possessed of no scant interest in the strange, mythical, and inscrutable.

In a 1982 essay, Calvino writes of Serafini’s “very clear italics,” which “we always feel we are just an inch away from being able to read and yet which elude us in every word and letter. The anguish that this Other Universe conveys to us does not stem so much from its difference to our world as from its similarity.” Clearly, “Serafini’s universe is inhabited by freaks. But even in the world of monsters there is a logic whose outlines we seem to see emerging and vanishing, like the meanings of those words of his that are diligently copied out by his pen-nib.” It all brings to mind a joke I once heard that likens humanity, with its invincible instinct to ask what everything means, to a race of space aliens with enormous trunks. When these aliens visit Earth, they respond to everything we try to tell them with the same question: “Yes, but what does that have to do with trunks?”

Related content:

An Introduction to the Codex Seraphinianus, the Strangest Book Ever Published

The Meaning of Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights Explained

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.